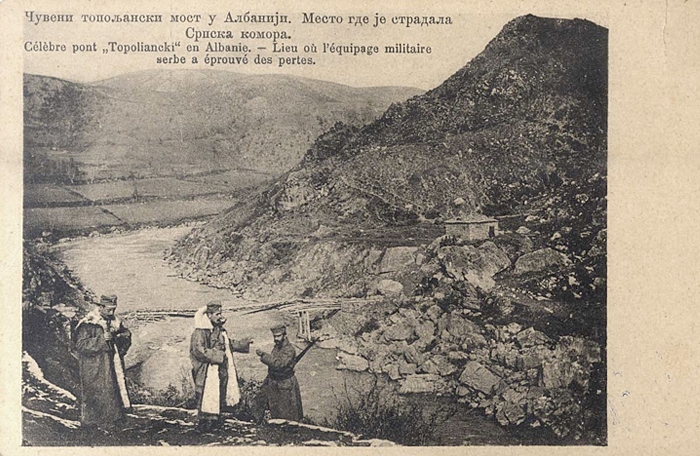

Over ‘The Damned’ Mountains, 1914

This is the story of my great grandmother and a trip she took not for pleasure, but for survival. Born in Serbia in 1894, the only daughter of a machinist, Anka Bojović was a strong-willed and independent child. She showed an affinity for teaching and finished her studies with ease. But the beginning of the 20th century was a tumultuous time. The First World War began, sparked by a swift Serbian bullet which took the life of the Archduke of Austro-Hungary. It changed her life's course and set her on the trip of a lifetime. When the Austro-Hungarian army retaliated against Serbia, they hit hard and the resulting occupation forced thousands to flee, along with King Peter and his troops. My grandmother was among them. Pregnant and unmarried, she joined the retreating army as a nurse and set out through Montenegro toward the mountain passes of Albania just as the cold set in.

The winter in the region is harsh, so harsh in fact, that half of those who tried to cross "The Damned" mountains (Prokletije) were left in the snow. Disease was rife and hunger an ever pressing concern, driving them to eat the horses that carried them. Anka was often forced to disguise herself and her growing belly, amongst the soldiers, wearing men's clothes and stuffing her boots with newspaper to prevent frostbite.

Many weeks later, the army and refugees reached Greece and the sparkling shores of the Mediterranean sea. They were greeted by locals with oranges—a sight for hungry eyes. The arrivals were quickly ushered to the island of Vido, dubbed "The Blue Tomb" for the bodies of the Serbs that were thrown into the sea when graves on land became scarce.

"The Blue Tomb" by Milutin Bojić (my rough translation)

"Stop, royal galleys! Drop your powerful masts! Step silently! I'm reciting a proud requiem in the shivers of the night above this sacred water. Here on the bottom, where sleep overcomes tired shells and moss gathers on lifeless algae, lies the cemetery of the brave, lies brother next to brother, Prometheuses of hope, apostles of misery.

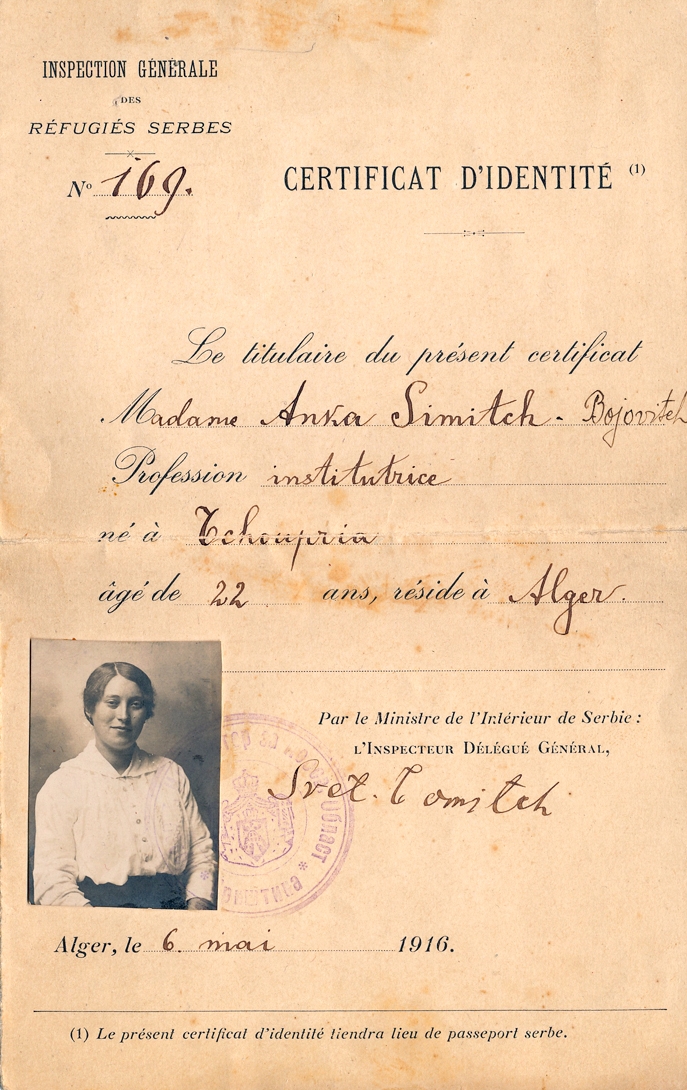

Soon after, many of the survivors were shipped to other allied countries. In Anka's case, she sailed for Algiers. She reached the French Colony just in time to give birth to a boy. The soldiers that traveled with her used this time to regain strength and later returned to triumph at the Macedonian Front. But Anka's joy was short lived. The baby Aleksandar (who my father is named after) lived for only 40 days and was buried at the Serbian military cemetery in Algiers. Some time later, Anka was joined by her child's wealthy father. It's a subject of much debate in the family as to why he left her to fend for herself until then. They married in Algiers in 1916.

Eventually, the family moved back to Serbia and Anka gave birth to a second child, my grandmother, Ivanka. Not one to succumb to societal pressures, Anka ended her unhappy marriage divorcing her husband before her daughter's first birthday. She returned to teaching to support herself and her little girl, continuing to travel from town to town and school to school, over the next 20 years. I can only hope that Anka's strength is hereditary, and I'm grateful to have the chance to tell her story.

Vido dubbed "The Blue Tomb"